Gasoline was discovered nearly 160 years ago as a byproduct of refining crude oil to make kerosene for lighting. Gasoline was not used at the time, so it was burned at the refinery, converted into gaseous fuel for gas lamps, or simply discarded. About 125 years ago, in the early 1890s, automobile inventors began to realize that gasoline had value as a fuel. In 1911, gasoline surpassed kerosene for the first time. And, by 1920, there were about nine million gasoline vehicles in the United States, and gas stations were opening across the country to fuel the growing number of cars and trucks. 1

Today, gasoline is the fuel of choice for light vehicles, which consume about 90% of the product sold in the United States. 2 Gasoline is also used in motorcycles, recreational vehicles, boats, small aircraft, construction equipment, power tools, and portable generators. Americans use an average of more than one gallon of gasoline per person per day, with U.S. consumption of about 392 million gallons per day as of December 31, 2016.3 So

, where does all this gasoline come from and how does it end up in automobile fuel tanks? Read on to learn more about gasoline manufacturing and distribution.

Gasoline is made from crude oil, which contains hydrocarbons – organic compounds composed entirely of hydrogen and carbon atoms. Crude oil has traditionally been obtained from vertical wells drilled into underground and underwater reservoirs. A well is essentially a round hole lined with a metal pipe called casing. The bottom of the casing has holes that allow oil from the reservoir to enter. Many oil wells also produce natural gas, which is primarily used for stationary applications like home heating, but can also serve as fuel with appropriate vehicle modifications.

Modern oil wells always start with vertical wells, but from there, they can branch out in multiple directions and at various depths. These lateral wells access additional oil, increasing production while minimizing surface disruption. Horizontal drilling is a common practice in hydraulic fracturing, a process that uses fluid injection and explosive charges to break up the ground around a well, which releases additional oil and natural gas. Horizontal wells can extend several miles from the central well.

While a few wells have natural internal pressure that pushes oil to the surface, most require some form of submersible or above-ground pump to remove the oil. Several additional processes can be used over the life of a well to extract the maximum amount of oil possible. Common secondary extraction methods include injecting water into the well and injecting gas or steam. When crude oil prices drop, low-production wells may be capped, to be brought back into service when prices rise.

Contrary to popular belief, the color of crude oil ranges from nearly clear to jet black and can have a viscosity ranging from that of water to nearly solid. The quality of crude oil also varies considerably, although oils from the same general area tend to have similar properties. Oil quality is based on a chemical analysis where the two most important values are molecular density and sulfur content.

Oils that have short hydrocarbon chains and a density of 34 or more on the American Petroleum Institute (API) scale are considered “light,” those between 31 and 33 are “medium,” while those 30 and below are “heavy.” Oils with a sulfur content below 0.5% by weight are “sweet” and those above that level are “sour.” Light, sweet crude oil is the most valuable type because it is more easily and cheaply refined and produces larger amounts of finished products.

There are 46 major oil-exporting countries, but crude oil prices are typically quoted based on one of three major benchmarks: West Texas Intermediate Crude, North Sea Brent Crude, and UAE Dubai Crude. The pricing of these benchmarks serves as a barometer for the entire oil industry. Oil prices are based on the cost of a 42-gallon “barrel” of crude, a unit of measurement that dates back to the dawn of oil drilling.

In the past, the United States imported large quantities of crude oil and other petroleum products. The peak was reached in 2005 when net imports (imports minus exports) reached 12.6 million barrels per day. More recently, ongoing exploration and advanced extraction processes have increased domestic oil production and reduced oil imports. In 2016, net imports were only 4.9 million barrels per day, equivalent to about 25% of total U.S. oil consumption. This is a slight increase from 24% in 2015, which was the lowest level since 1970 4.

Once crude oil is extracted from wells, it is stored in large tanks before being transported to refineries. Pipelines, ships, and barges are commonly used methods to move crude oil. However, in recent years, increased production in areas lacking pipeline or waterway access has resulted in more oil being transported by train in tank cars. Very thick and heavy forms of crude oil, such as oil sands, must be diluted with solvents before they can be pumped into pipelines or transported by other means.

All methods of transporting crude oil carry potential environmental risks. However, oil train derailments present additional risks as trains regularly pass through towns and villages where oil spills and potential fires could cause significant property damage and loss of life.

To address these concerns, the Department of Transportation issued a comprehensive final rule in May 2015 that contained enhanced standards for tank cars, new operational guidelines for moving large volumes of flammable liquids by rail, and improved emergency response planning and training. The railroad industry supports the accelerated replacement of older tank cars, has increased track inspections to minimize derailment risks, and has adopted special technology to help determine the safest rail routes for transporting oil.5

Refineries are large-scale industrial facilities that produce commercial products from crude oil and, in some cases, other feedstocks such as biomass. More than half of U.S. oil refining capacity is located on the Gulf Coast, with the remainder scattered across the country – typically near oil production sources or transportation pipelines and waterways.

Oil refineries operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but must be shut down periodically for maintenance and repairs. Generally, this occurs in the spring and fall when changes need to be made to refineries to switch from summer to winter gasoline production, and vice versa. The differences between the two will be discussed later.

Refinery shutdowns impact regional gasoline supply, so they are typically planned well in advance and closely monitored. This allows the distribution network to make the necessary adjustments to ensure an uninterrupted fuel supply. Unplanned refinery outages caused by technical issues or extreme weather conditions can lead to short-term localized gasoline shortages and higher fuel prices.

Almost all gasoline sold in the United States is refined here, and the U.S. also exports large quantities of gasoline to other countries – over 230 million barrels in 2016.6 Refining crude oil into finished petroleum products is an extremely complex undertaking. The following description provides a high-level overview of the refining process, focusing on gasoline production.

All refineries use a primary process called fractional distillation to break down crude oil into various components. Distillation involves heating crude oil to boiling (around 600°C) and then injecting the vapor into a distillation tower. As the hot vapor rises in the tower, it cools, and at different heights and temperatures, various “fractions” of the crude oil condense and are collected. Heavier fractions, such as lubricating oil, have higher boiling points and condense near the bottom of the tower. Lighter fractions, such as propane and butane, have lower boiling points and rise to the top. Gasoline, kerosene, diesel, and diesel fuel are collected in the middle section of the tower.

Very few petroleum products, including gasoline, are ready for use when they come out of the distillation tower. A number of secondary refining processes are required to purify the fractions and convert them into marketable products.

“Cracking” involves processing methods that break down the molecules of heavier fractions into lighter fractions. It is frequently used to make gasoline components from heavier oils. There are many forms of cracking such as fluid catalytic cracking, hydrocracking, and coking/thermal cracking. Each results in unique hydrocarbon chains that are used in gasoline and other products.

“Combining” is essentially the opposite of cracking. It unites lighter fractions into heavier fractions that are also used in gasoline formulation. Two common combining processes are reforming and alkylation. The former increases the amount of components that go into making gasoline, while the latter creates “aromatic” hydrocarbons that play a key role in increasing the octane of the finished fuel.

The final step in gasoline production is blending. Several petroleum products from the various refining processes are carefully combined to create regular and premium grade base gasolines. These fuels must meet explicit and extensive performance requirements that change both with the season and the location where the fuel will be sold. For example, summer gasoline is blended to vaporize less easily, which helps reduce evaporative emissions. Winter gasoline is blended to vaporize more easily, which aids in cold engine starting and drivability.

Several regions of the United States require specially blended “boutique” or “reformulated” gasolines that burn cleaner and are part of a State Implementation Plan (SIP) to reduce emissions. Originally, there were 15 unique formulations, but in an effort to reduce the proliferation of gasoline blends, the EPA now only allows six boutique fuels to be used in new SIPs. 7 Other formulations that are part of existing SIPs continue to be used in various areas.

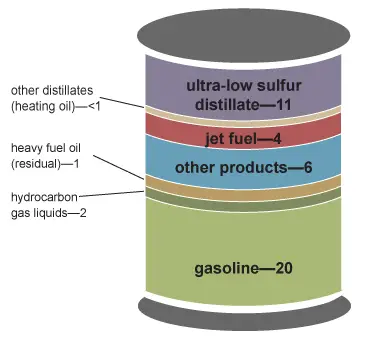

The amounts of finished petroleum products made from a barrel of crude oil vary by refinery, but most plants are designed to maximize gasoline production. As the accompanying illustration shows, nearly half of each barrel is converted into gasoline, with about a quarter becoming diesel fuel (ultra-low sulfur distillate). Due to an effect called “refinery processing gain,” a 42-gallon barrel of crude oil will actually yield about 45 gallons of finished petroleum products.